-

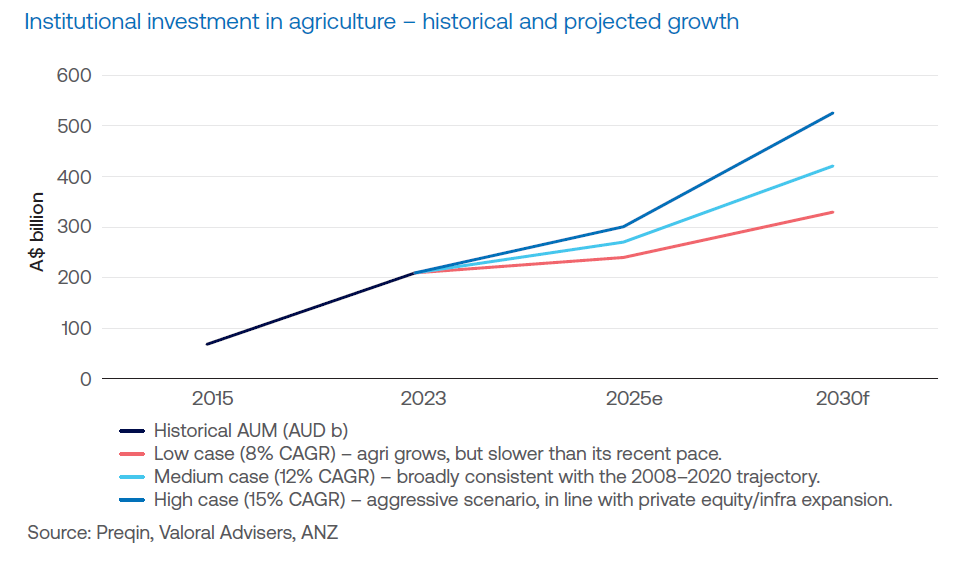

By some estimates, global institutional exposure to agriculture — including land, water, infrastructure and natural capital — could exceed $A500 billion by 2030. This reflects a broader definition of agri assets, encompassing not just farmland but supply chain investments and environmental markets.

It wasn’t always this way. In 2008, the world faced a food crisis. Global grain supplies had quietly tightened, attracting little attention. Then, stockpiles collapsed and prices surged.

Corn and soybeans were increasingly diverted into biofuel production, leading to concerns about ‘food versus fuel’ and whether there would be enough grain to feed both people and energy markets.

At the same time, rice reserves — critical for food security across much of Asia — fell to dangerously low levels. The price of rice tripled, while corn and wheat doubled, forcing governments to impose export bans and igniting food riots.

For institutional investors, this was more than a supply chain shock. It reframed agriculture as something far more significant than a traditional commodity trade. Land, water and food were no longer simply production factors - they had become investable assets tied to long-term returns, resource scarcity and the shifting balance of global food security.

Almost 20 years later, the agricultural investment landscape has transformed. What began as a niche allocation for a handful of early movers has become part of mainstream real asset strategies.

In 2025, the industry is entering a more complex phase. After more than a decade of land value appreciation and post-COVID commodity surges, conditions have tightened.

Across many regions, farmland prices have plateaued. Input costs - from fertiliser to diesel to labour - remain structurally high. Commodity markets, once buoyed by post-pandemic demand, have come off their peaks.

Investors are now facing thinner margins and increased volatility. The central question is no longer whether agriculture belongs in institutional portfolios but how to structure exposure when potentially the easy gains have already been captured.

On the radar

Before 2008, agriculture was barely on the radar of most large institutional investors. A few Australian super funds and New Zealand vehicles held pastoral leases or cropping assets, although these were typically legacy holdings.

Some United States (US) university endowments, such as Harvard and Yale, included timberland or farmland in their portfolios for diversification. Private families and local investors often backed food businesses or held agricultural land directly.

Earlier decades saw corporate ownership in agriculture — companies like Elders, Dalgety and CSR once owned extensive rural assets in Australia, while Cargill and Louis Dreyfus operated large-scale global trading and processing businesses. Large-scale capital flows from global financial institutions into farmland and food systems were rare prior to the crisis.

That all changed after the crash. Biofuel mandates in the US and Europe led to concerns about food versus fuel, as corn and soybean crops were diverted into ethanol production. Poor harvests in key grain-producing regions and historically low stock-to-use ratios, particularly for rice, pushed prices higher. The global food system revealed its fragility.

For investors, three facts stood out. Global food demand was structurally rising. Productive land was finite and under-owned by professional capital. Agriculture offered diversification from traditional asset classes, an inflation hedge and a physical asset base.

Between 2008 and 2013, global agri investment accelerated. Canadian pension funds like PSP (Public Sector Pension Investments) and the AIMCo (Alberta Investment Management Corporation), US-based TIAA (Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association of America) and Dutch pension funds like APG (Algemene Pensioen Groep) began acquiring large-scale cropping and grazing portfolios.

Sovereign wealth funds from the Gulf and Asia followed. For these investors, food security was often as important as financial return. Entities like SALIC (Saudi Agricultural and Livestock Investment Company) and Temasek (Singapore) backed deals that provided supply chain access, particularly for protein and grain.

Private equity and family offices also entered the space. Some targeted permanent plantings – like almonds, macadamias or vineyards - that matched long-term fund lifecycles. Others pursued scalable cropping or pastoral assets in Australia, the US or Latin America. Endowments like Harvard invested heavily in Brazilian farmland and California vineyards, though later retreated after governance challenges.

Australia became a global hotspot for agri investment. The attraction was clear: stable regulation, clean biosecurity status, counter-seasonal production and close ties to Asia.

Between 2010 and 2022, broadacre land values rose by more than 220 per cent. Major players moved in. Macquarie established Paraway Pastoral in 2007, creating one of the country’s largest diversified grazing and cropping enterprises. PSP expanded its Australian agriculture portfolio separately, building significant holdings across cropping, livestock and permanent plantings.

Water entitlements were bundled into many transactions, particularly in horticulture, where investors saw long-term value linked to reliable irrigation. Farm consolidation accelerated. As Australia’s farming population aged, many operators sold.

Investors aggregated properties, converting grazing land to cropping, capturing productivity gains and valuation uplifts. For much of this period, the play was simple: buy assets, drive scale efficiencies and watch capital values rise.

By 2024, the landscape had shifted. After years of strong appreciation, land values in many regions plateaued, with recent sales delivering only modest gains. Input costs remained high, as fertiliser and fuel prices failed to return to pre-COVID levels, and labour shortages drove up wages.

Commodity prices also retreated. Wheat markets, after spiking due to conflict in Europe, stabilised and then fell by around 30 per cent from 2022 highs. Beef prices softened in several markets as supply normalised, while in the US tight cattle numbers kept prices firm. Cotton and almonds, tied to global production cycles and discretionary spending, remained volatile.

For investors accustomed to rising land values and commodity tailwinds, the shift was clear. The focus moved from capital appreciation to yield, resilience and operational performance.

Rethinking

Institutional capital behaves differently across agriculture. Differences are driven by mandate, risk appetite, time horizon and public accountability. Pension funds, such as PSP or Australia’s Aware Super, prioritise stable, inflation-linked income streams aligned with long-term liabilities. Many prefer leaseback models or co-investment partnerships, capturing land-linked yields without the operating risk or partnering with specialised management

Sovereign wealth funds, including ADIA (Abu Dhabi Investment Authority) and SALIC, operate under dual mandates: financial return and strategic security. For many, securing strategic access to food supply chains is as important as profit. These funds often tolerate longer payback periods if the investment aligns with national food policy goals.

Family offices represent a diverse group. Some pursue regenerative agriculture or premium food exports for legacy objectives. Others focus on scalable cropping or horticulture, often linked to water entitlements.

Endowments, particularly in the US, were early movers. Following the global financial crisis, institutions like Harvard invested heavily in Brazilian farmland, Californian vineyards and US Midwest cropping. Some have since reduced exposure, particularly where social licence or governance risks became concerns.

Private equity (PE) takes a different approach. With shorter fund lifecycles - typically five to seven years - PE firms avoid pure land plays unless there is clear value-add potential. Instead, they invest in assets that generate margin growth through operational improvement, branding or market expansion. KKR’s (Kohlberg Kravis Roberts) acquisition of poultry giant ProTen is an example.

Agri portfolios are now broader. For many funds, the play is no longer just land — it is the whole system. Storage infrastructure, processing plants, cold-chain logistics and water entitlements are now common in institutional portfolios.

Australia remains a premier destination for global agri capital, but challenges persist. Foreign pension funds, sovereign wealth entities and global asset managers remain active. In contrast, most Australian superannuation funds have been cautious.

Despite managing over $A3.7 trillion, Australian super funds have limited direct exposure to agriculture. This reflects the difficulty of matching large-scale capital to fragmented, often illiquid agri assets.

Most super funds need to deploy hundreds of millions of dollars at a time into assets with stable, long-term returns and clear exit pathways - such as infrastructure projects with 20-year contracts or commercial property with secure lease agreements.

Agriculture, especially farming operations, does not always meet these requirements due to seasonal volatility, operational complexity and less-predictable exit options.

Liquidity is also a factor. Unlike infrastructure or real estate, which often come with long-term contracts, agricultural returns can fluctuate seasonally. This complicates long-term exposure for funds balancing member redemptions.

The debate over foreign ownership has also evolved. In the early 2010s, headlines focused on national sovereignty and food security. Today, the focus is more pragmatic. Most capital providers — foreign or domestic — operate through joint-ventures or local management. The discussion has largely shifted from ownership to management quality and sustainability.

Questions remain about how to unlock domestic superannuation capital for agriculture. Some industry leaders, fund managers and policymakers have suggested shared investment models, where super funds partner with experienced farm operators or specialist managers to invest alongside each other, reducing risk and management burden. Others point to the growth of natural-capital markets as a way for Australian funds to participate with less exposure to agricultural volatility.

What next?

Agri investing has matured from a growth story to a game of operational excellence and resilience. Arguably, the easy wins of land aggregation and capital gain have passed. The future depends on building strategies that deliver yield in a complex environment, adapt to climate risk and navigate a volatile food system.

The fundamentals remain. The world’s population continues to grow, Asia’s middle class is expanding, and food security has become central to long-term investment strategies across supply chains.

For investors with the right capital and structure, agriculture still offers real returns — although the future of agri investing is no longer just about land but managing the whole system.

James Dunnett is Director - Food, Beverage & Agriculture at ANZ Institutional

This is an edited excerpt from the Spring 2025 edition of the ANZ report “Food for Thought”

Receive insights direct to your inbox |

Related articles

-

The US is unlikely to replicate the UK’s post-Brexit direction - but some rhyming seems likely, in time.

2026-01-27 00:00 -

The year 2026 is not without risks - but considerably fewer risks than 2025.

2026-01-20 00:00 -

The global macro environment has been more supportive than expected, and another solid year is in prospect.

2026-01-09 00:00

This publication is published by Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited ABN 11 005 357 522 (“ANZBGL”) in Australia. This publication is intended as thought-leadership material. It is not published with the intention of providing any direct or indirect recommendations relating to any financial product, asset class or trading strategy. The information in this publication is not intended to influence any person to make a decision in relation to a financial product or class of financial products. It is general in nature and does not take account of the circumstances of any individual or class of individuals. Nothing in this publication constitutes a recommendation, solicitation or offer by ANZBGL or its branches or subsidiaries (collectively “ANZ”) to you to acquire a product or service, or an offer by ANZ to provide you with other products or services. All information contained in this publication is based on information available at the time of publication. While this publication has been prepared in good faith, no representation, warranty, assurance or undertaking is or will be made, and no responsibility or liability is or will be accepted by ANZ in relation to the accuracy or completeness of this publication or the use of information contained in this publication. ANZ does not provide any financial, investment, legal or taxation advice in connection with this publication.